By Phil Roberts

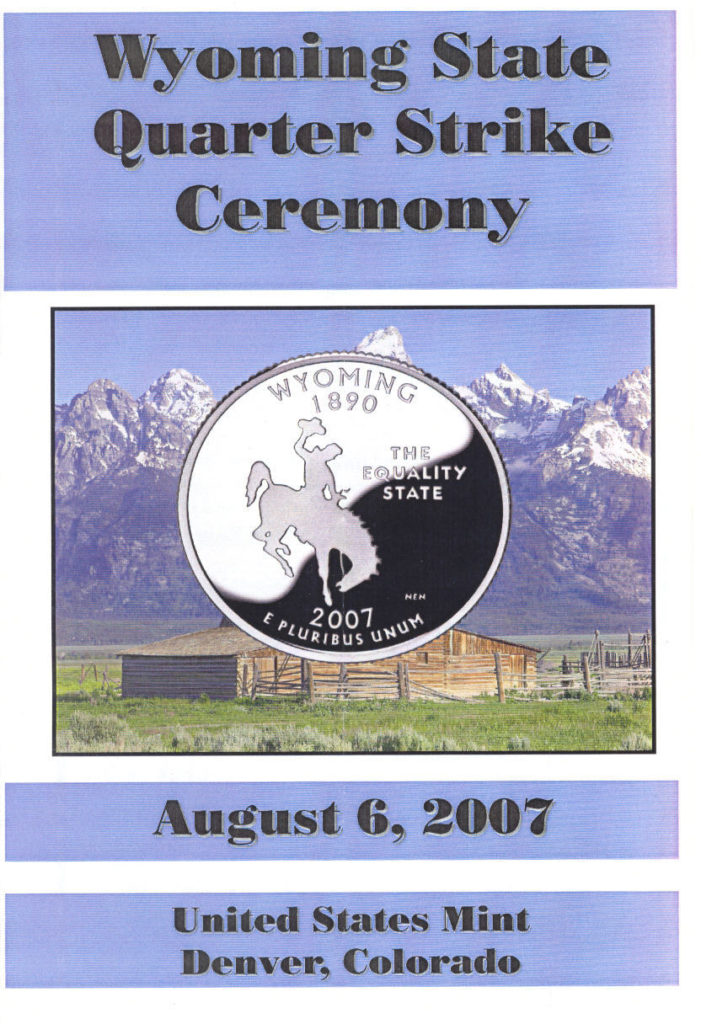

The new Wyoming quarter, officially unveiled in August 2007, shows Wyoming’s license-plate bucking horse and next to it are three words: “The Equality State.”

It’s not the only place where the seemingly contradictory nicknames seem to joust for dominance. The legislature designated the state officially as “the Equality State” back in 1935 (but appearing much earlier in that body), but even Wyoming Public Radio referred to Wyoming with the more “tourist-friendly” nickname, “The Cowboy State.”

The cowboy is an image that has been with us for a very long time. The bucking horse went on the license plate in 1935—the first logo on any license plate in America.

If a state has a “self-image” (something I often question), are we more drawn to one than the other? “Cowboy State?” “Equality State?” Doesn’t one cancel out the other? Are these contradictions?

I say the two nicknames represent remarkably compatible concepts. In modern times, the image of the cowboy has taken a beating, becoming stereotyped, for good or bad, as a term denoting reckless foreign policy, for instance, or fiercely intolerant and destructive acts against the environment.

But like all stereotypes, this one is wrong when you look at history. Open-range cowboys in frontier Wyoming came from every racial and ethnic group. Most didn’t have anything except a saddle and a backpack—and sometimes, his own horse. Unlike farmers who tried to change the environment by clearing land and digging irrigation ditches or miners that dug big ugly holes in the ground, the cowboy lived with the environment. He put on a slicker when it rained, tied his hat down tight with a bandanna to keep the winter winds at bay, and tried to protect his charges from thirst, snow-blindness, and wolves. He knew he couldn’t change the environment; he just had to live with what it dealt him.

And the equality part? It was initially intended to commemorate Wyoming’s first role in granting the vote to women.

But it also reflects on the spirit of the cowboy. Mostly, he judged other cowboys by how well they rode, whether they paid you back if you loaned them a quarter for cigarettes, how hard they worked, and whether you can count on him to watch your back in a fracas. Every man had to prove himself, regardless of race or ancestry. It didn’t matter how great one’s family was. Or as my grandmother used to say, “Every tub sits on its own bottom.”

But there are awful lapses in how Wyomingites have dealt with “equality.” From the Rock Springs massacre to the Black 14 and Mathew Shepard, some would say “equality” isn’t a nickname Wyoming deserves. I disagree.

“The cowboy state” ought to reflect the non-stereotypical past—when being a cowboy meant honor, capacity for hard work, and respect for the individual. In some ways, it is “historical”—a touchstone to look back to for inspiration. It is retrospective—even a mythical way for us to identify with the past.

And the “equality state”—that nickname is aspirational—a goal toward which we ought to be striving. While we likely will continue to come up short, being mindful of striving for equality ought to continue to make us not only a more humane society, but conscious of our state’s reputation for friendliness to visitors, for tolerance of other’s views—and for valuing individual differences.

And the two nicknames aren’t contradictory. As we aspire to greater equality, we need to remain true to the “cowboy” way that brought us this to this point—not just the Hollywood version, but what came from the reality of the Wyoming cowboy of the open-range days.

And the open space so often crowded out on other coins with words, symbols, logos—they are intentional for Wyoming, indicating the wide-open spaces of the least populated state.

With the “bucking horse” and the Equality State sharing the same open space, it makes a good deal of sense. After all, they belong side by side, both on the same coin.